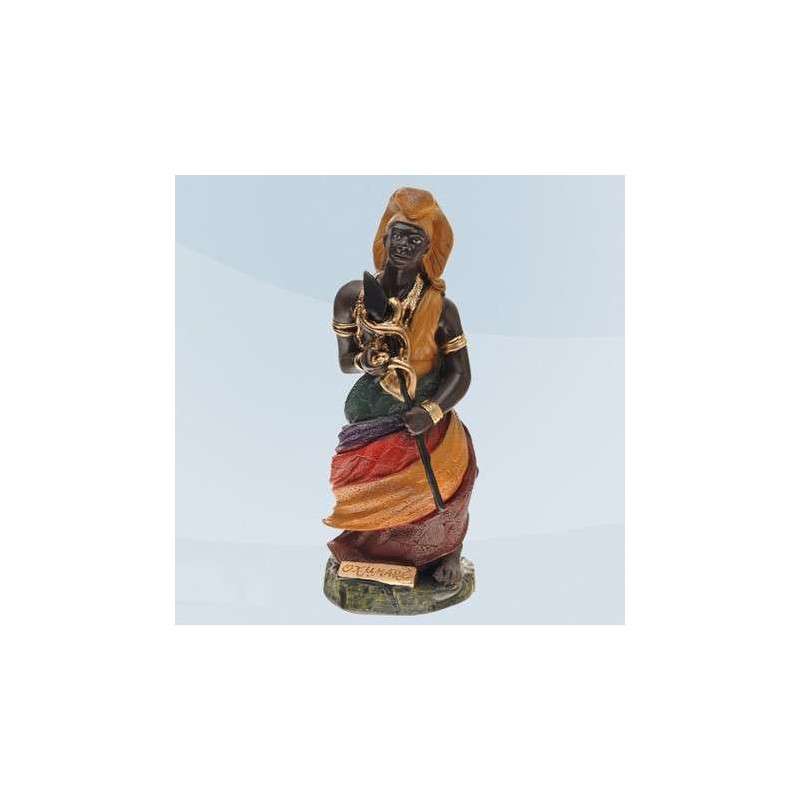

Image of Oxumaré

Material: Hand-painted plaster.

Size: Approximately 23 cm tall.

Security policy

Delivery policy

Connects heaven and earth, controls rain, soil fertility and harvest abundance. Oxumarê is an Orixá that is highly worshiped in Brazil, although there are many confusions about him, especially in syncretisms and in cults that are more distant from traditional African candomblé such as Umbanda. The confusion starts with the name itself, since part of it is also the same as the name of the female orixá Oxum, the lady of fresh waters. Some Umbanda currents even say that Oxumarê is one of the different forms and types of Oxum, but in traditional candomblé such an association is absolutely rejected. They are distinct deities, including in terms of cults and origin.

Regarding Oxumarê, any stricter definition is difficult and risky. It cannot even be said that he is a male or female orixá, as he is both things at the same time: half the year is male, the other half is female. For this very reason, duality is the basic concept associated with its myths and archetype. This ubiquitous duality makes Oxumarê carry all opposites and all basic antonyms within itself: good and evil, day and night, male and female, sweet and bitter, etc... In the six months in which it is a male deity , is represented by the rainbow which, according to some legends, is the point that allows the waters of Oxum to be taken to the castle in the sky of Xangô. In the following six months, the orixá takes on a female form and approaches all the opposites of what it represented in the previous semester. He is then a snake, obliged to nimbly drag himself both on land and in water, leaving the heights to always live close to the ground. In this form, according to some myths, Oxumarê incarnates his most negative figure, provoking everything that is bad and dangerous.

Oxumarê is the orixá of movement, action, eternal transformation, the continuous oscillation between one path and another that guides human life. He is the orixá of thesis and antithesis. Therefore, his domain extends to all regular movements, which cannot stop, such as the alternation between rain and good weather, day and night, positive and negative.

Certain houses in Umbanda and certain janitors have in their cults the absence of the orixá Oxumarê. Those who think that Oxumarê is not part of the cults of Umbanda are mistaken. He is the orixá of the seven colors of the rainbow, and that is why he brings in his essence the seven lines within Umbanda. He is the orixá of colors and of all that is beautiful. There is no altar without roses and there is no rose without color. There is present Oxumarê. In superficial terms, one can also associate the rainbow with good and the snake with evil because if the first is a colorful, beautiful image, which brings aesthetic pleasure to people, the second is a dangerous animal, which can lead to the man to death.

Another source of identification regarding the Orisha comes from the contradictions existing in their legends. It turns out that the origin of the Orisha is one of a different culture from most of the orixás worshiped in Brazil and in Africa itself. Oxumarê is a deity originating from the culture of Dahomey, in the central-north region of Africa. Centuries ago, this civilization was dominated by the Yoruba, a more primitive people in the sense of social organization and religious vision, but, on the other hand, more powerful in terms of military organization. As happened with Rome and Greece, the political domination of a society less rich in cultural productions or in the field of superstructure in general meant that the myths of the Dahomeans were not only repressed. On the contrary, the Yoruba did not try to impose their culture on the dominated people. They were, in fact, impressed by its cosmology and tried to assimilate it, mainly in the figures that were not similar forms to the deities that they also possessed. At the same time, there is a basic difference between Dahomey culture and the Yoruba view of deities in general. If the warrior figures of a sensual and enraptured Ogun, an explicit and frank Iansã or a cleverly malicious and diplomatic Oxum are easy to understand, forming clear archetypes, the Dahomey orixás are more somber, mysterious. Their legends do not quite present them as the legends of the Nagô.

There is always a somewhat hidden territory, something secret, mysterious, in their behavior, a whole range of ambiguity that does not allow for a definition as accurate and simple as that of the orixás of the Yoruba country. The gods of Dahomey are more punitive, circumspect, austere and vindictive. They are not only carried away by the passion of the most common figures in the Yoruba world, who, in the same way that they punish devastatingly, dramatically regret what they have done to human beings. No, Oxumarê, Iroko, Omulu, Obaluaiê and Nanã, the best known and most worshiped Dahomey orixás, punish when willing or provoked, but they rarely repent and do not have the laughable and humanizing flaws of the figures of the Yoruba pantheon. Because its "appearance" as a snake and as a rainbow in rivers and waterfalls is common, Oxumarê